If you’re new here from my Fernanda Melchor piece at The Metropolitan Review, welcome!

One of my favorite classes to teach at the University of Detroit Mercy is English 2350: Study of Fiction, a core curriculum class that students take to fulfill one of their core requirements. Most of the students are not English major or minors, instead coming from STEM, Health Sciences, Architecture, and Business. The students, for the most part, are happy to take a break from classes in their majors and when the chemistry is right and everything clicks, the multitude of disciplinary perspectives can lead to such a textured, and sometimes surprising, discussion. Because my classes are conversation based there is always a strong element of chance and surprise, which makes the discussion feel real and meaningful, although this comes with an element of risk: what if a student identifies with the “wrong” character, for instance, or what if they reject the overall worldview of the story? But even these fraught moments can lead to a larger understanding of questions like: can a story be “misread?” What are the boundaries and limits of interpretation which is, after all, subjective, involving a sort of collaborate meaning-making in the classroom?

Because Study of Fiction, thankfully, does not limit the fiction under consideration—there are no rules about the genre of fiction, or time period, or nationality—I always include several translated novels or stories. I’ve taught several stories by Enriquez over the years, but always come back to “The Things We Lost in the Fire” because it’s so dimensional and layered and teachable not only in terms of content (women in Argentina, as a protest against femicide, begin burning themselves as a collective act of resistance, and also perhaps to usher in “a new kind of beauty”) but also because it’s a beautiful example of close third-person narration. Although we largely experience the story through eyes of Silvia—a young woman whose mother is fully supportive of the protests, but who herself has growing qualms about the immense self-damage the fires cause—the story isn’t narrated by her. Instead, we dip into her mind from just outside:

Silvina vaguely remembered the news reports, the gossip around the office. He had burned her during a fight, they said.

Once the cameras had gone, Silvina’s mother approached the subway girl and her companions. Several of the women were over sixty years old, and Silvina was surprised to see them so willing to spend the nigh in the street, to camp out on the sidewalk and paint their signs saying WE WILL BE BURNED NO MORE.

It becomes more beautifully complicated when we enter into a kind of unannounced interior monologue, as we shift from Silvina’s thoughts being described to us to actually falling into the stream of those thoughts:

Since when did people have a right to burn themselves alive?

The phrasing isn’t Since when did people have a right to burn themselves alive, she thought. There is no dialogue tag, no “she thought” or “she wondered.” Her question just appears, unadorned.

But something strange happens at the end of the story:

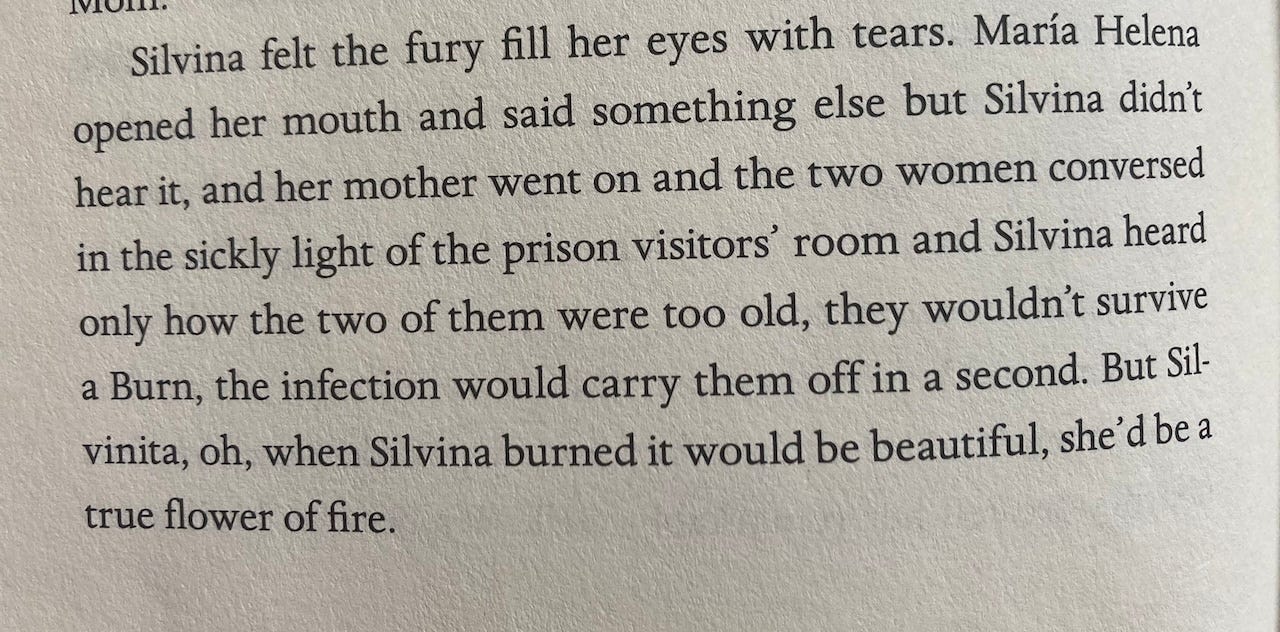

It seems as if the close third shifts—maybe for the first time in the story—to Silvina’s mother’s point of view. This is weirdly troubling and is part of what makes “Thing We Lost in the Fire” so unsettling and memorable. It’s like a little sliver of thought that just won’t work itself out, pinning the story in your brain. Silvina has joined her mother in a visit to a prison to visit María Helena, a contemporary of Silvina’s mom who has been encouraging, protecting, and treating the girls who burn themselves and who suggested that it may take from forty thousand to hundreds of thousands of burnings (the estimated number of witches burned during the Inquisition) before the protests end. Silvina listens to this conversation between María Helena and her mother (perhaps increasingly horrified at the scope of the burnings they are imagining) and it’s María Helena who uses the word “oh” (“Oh, what do I know, child. If I had my way they’d never stop!”), a word echoed in the last line (“oh, when Silvina burned”), as if her daughter’s burning is a foregone conclusion.

So, it seems like the final paragraph begins “with” Silvina (“Silvina felt the fury . . .”) and ends with her mother "(“when Silvina burned . . .”) but this happens so invisibly that we are carried along by what Jane Alison, in Meander, Spiral, Explode: Design and Pattern in Narrative (2019) calls “wavelets”: a wave in miniature, or what she also calls “dispersed patterning.”

This little wave, this shift in point of view from Silvina to her mother, is so gentle, so artfully feathered into the story, that it’s easy to miss. This slippage in the very last paragraph from Silvina’s general point of view to her mother’s—without warning or announcement—takes the story’s terror to a new level, suggesting that Silvina’s mother will see to it that Silvina burns, despite Silvina’s growing doubt and “fury” at what the women are doing. This complicates the entire worldview or position of the story, which unfolds as a sort of dark parable “on the side of” the women who burn themselves as an extreme form of protest against the brutal—but normalized—violence against women. Is Silvina’s mother—so sympathetic to the cause of the Burning Women—one of the monsters in the story? I don’t think so, but it’s a question I’m prompted to ask by that last paragraph.

The first time I read the story I think I was guilty of misreading it, imposing on it a clear-cut dystopian template where, of course, we are supposed to identify wholly with the self-immolation protests, accepting the self-violence—in the world of the story—as a legitimate response to the larger, structural evils of femicide. This misreading may have have even carried me so far as to overwhelm the story’s ending into reading it as Silvina’s own internal voice and translating it into something like: “oh, when I [Silvina] burned it would be beautiful, I’d be a true flower of fire.”

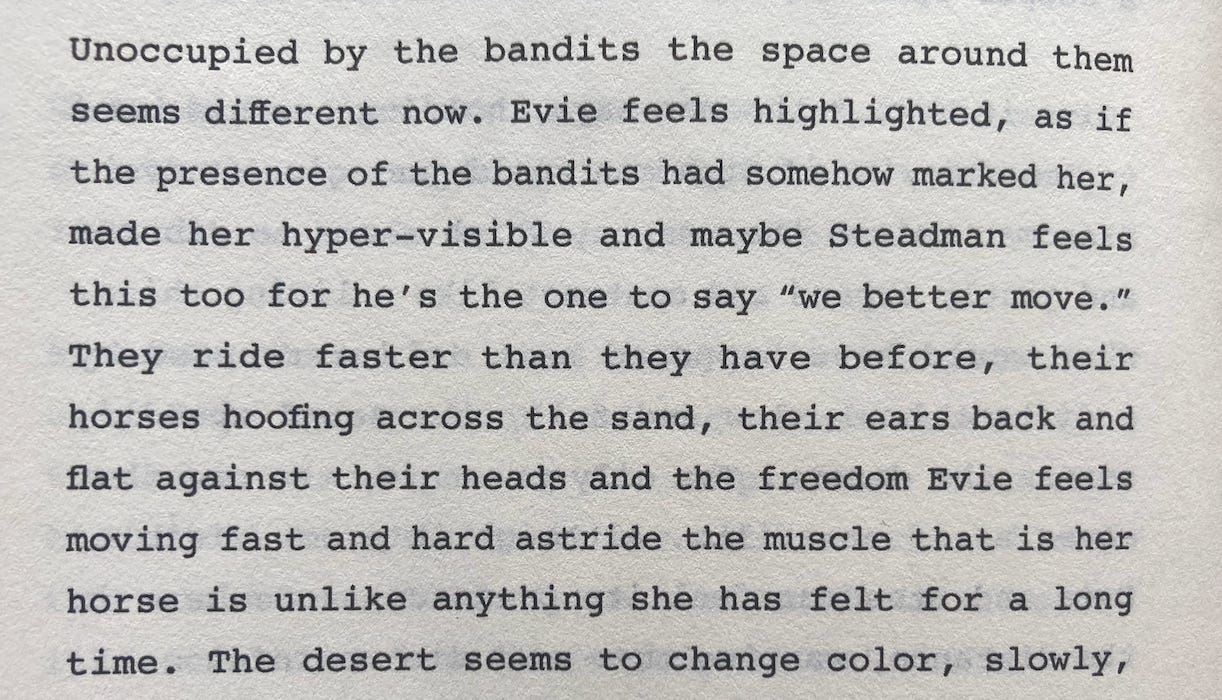

I wonder if, sometimes, a misreading can be productive? Productive misreading. I’m so obsessed with this it finds its way into my own fiction, especially The Rachel Condition (CLASH Books), where the third-person closeness to one of the characters, Evie, allowed me to be in her head without succumbing to the psychological claustrophobia of first-person narration:

I had tried this section of the novel in first person; it didn’t work because I wanted us to be with Evie but not consumed by Evie and her thoughts. What floors me about Enriquez’s work (and Our Share of Night takes this to a whole other level) is the seamlessness by which she guides us through such subtle but powerful narrative gear changes. Little wavelets that, cumulatively, drift us into uncharted territories.

It makes me want to fall into the worlds Enriquez creates.

Again and again.

Is it OK to view a close third perspective as a limited perceptible region within an omniscient third? If an omniscient third stays close to a single character for the vast majority of a novel, but shifts away from this constraint at strategic points in the narrative, might its close third proximity be characterized as a choice within omniscient's grand geography?

Fascinating stuff, especially on the heels of your essay about Melchor, whom I love. I just finished This Is Not Miami and thought of Enriquez often.